How Does Temperature Affect Solenoid Valve Coils and Performance?

2025-11-20I am a factory owner from China with over a decade of experience running 7 production lines dedicated to manufacturing high-quality hydraulic valves. I’ve worked with countless buyers like Mark Thompson from the USA—professionals who know the business side of machinery but might not be hydraulic engineers. One question that often comes up, usually after a part has failed unexpectedly in the field, is about temperature. Specifically, how heat or extreme cold impacts the life and reliability of a valve.

This article is worth reading because temperature is the silent killer of hydraulic components. It can burn out a coil, freeze a seal, or cause a machine to lose power when it’s needed most. Whether you are buying for construction equipment in Arizona or cold storage forklifts in Norway, understanding the relationship between the solenoid valve, the coil, and heat will save you money and protect your reputation. We will explore how solenoid valve coils handle heat, the impact of the environment, and how to choose the right temperature rating to prevent failure.

Why Do Solenoid Valve Coils Generate Heat During Operation?

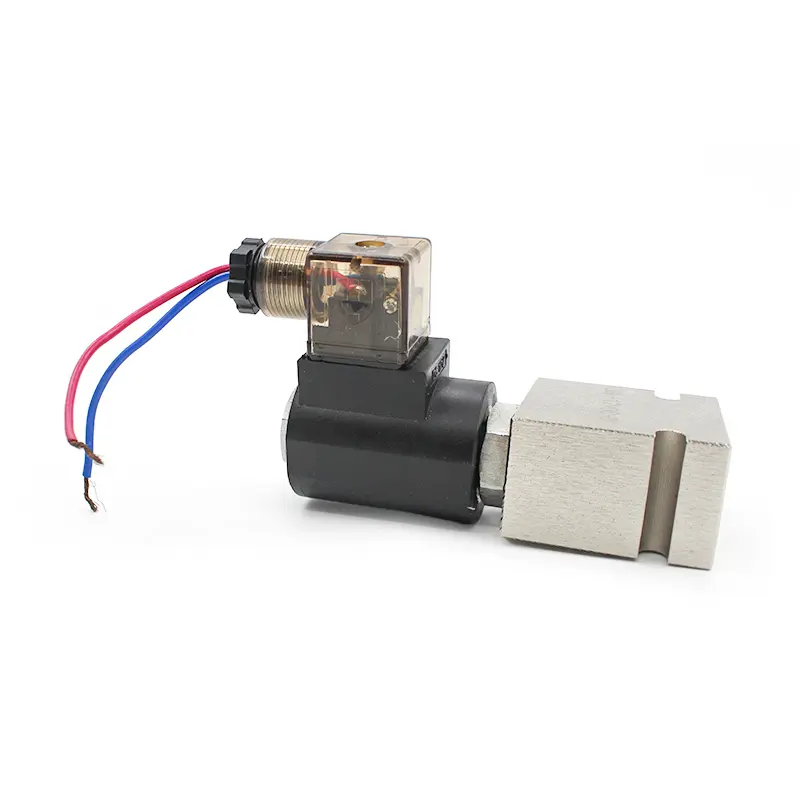

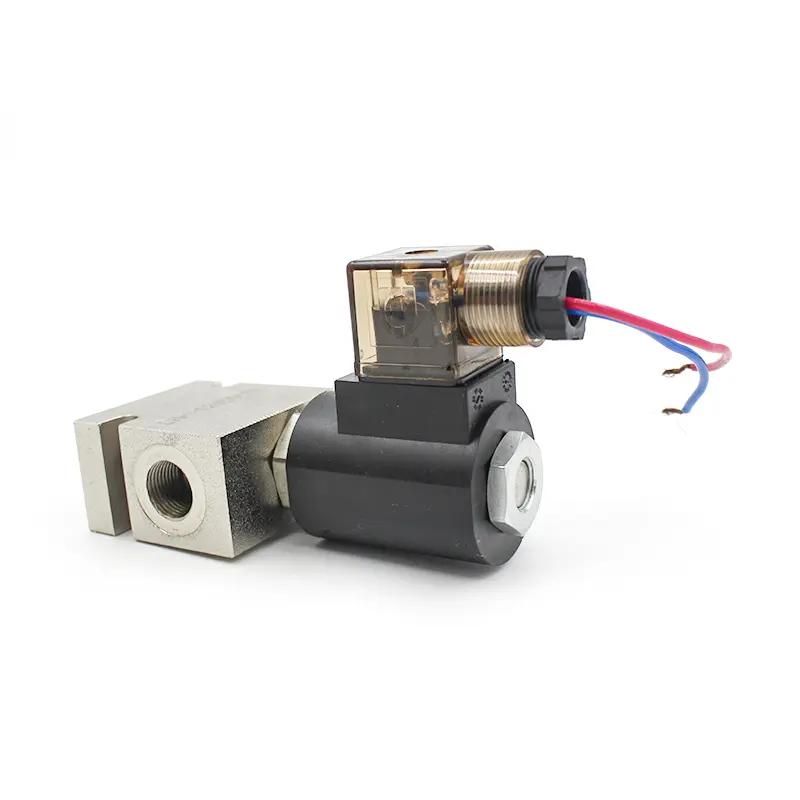

To understand why a solenoid valve gets hot, we first need to look at how it works. A solenoid is essentially an electromagnet. It consists of a copper wire wound tightly around a bobbin to form a coil. When you apply an electrical current to this wire, it creates a magnetic field that moves a plunger to open or close the valve. However, the wire has electrical resistance. Think of resistance like friction for electricity. As the current fights to get through the wire, that energy is converted into heat.

This internal heating is completely normal. Every solenoid valve will experience a temperature rise when it is energized. This is often referred to as "Joule heating" or resistive heating. The amount of heat generated depends on the voltage applied and the resistance of the coil. If a valve is designed for continuous duty (meaning it stays on for hours at a time), it must be able to dissipate this heat effectively. If the heat builds up faster than it can escape, the temperature inside the coil will spike.

The design of the solenoid valve coils is a balancing act. We need enough copper wire to create a strong magnetic force to operate the valve, but we also need to manage the heat that comes with it. In my factory, we use high-grade copper and specialized insulation materials to ensure that this self-generated heat doesn't damage the valve components. If you touch a solenoid after it has been running for a while, it will feel hot. That is the physics of electricity at work.

How Does High Ambient Temperature Impact Solenoid Performance?

The internal heat generated by the coil is only half the battle. The solenoid valve must also live in the real world. The ambient environment—the air temperature surrounding the valve—plays a massive role in solenoid valve performance. A solenoid relies on the surrounding air (or the metal it is mounted to) to cool down. Heat naturally flows from a hot object to a cooler one.

If the ambient temperatures are very high, perhaps because the machinery is operating in a desert or the valve is mounted next to a hot engine block, the coil cannot shed its internal heat. It’s like trying to cool off on a hot summer day while wearing a winter coat. The heat stays trapped inside. This causes the total temperature of the coil to rise significantly higher than the manufacturer intended.

When the temperature gets too high, several bad things happen. The insulation on the copper wire can melt or become brittle, leading to a short circuit. The magnetic force can actually weaken (we will explain this more later), causing the valve to fail to open or close. In hot ambient conditions, we often recommend using a coil with a higher temperature rating or ensuring there is airflow around the valve to help it breathe. Ignoring the ambient heat is a common cause of valve failure.

Can Fluid Temperature Affect the Solenoid Valve Seals?

While the coil sits on top, the valve body is handling the fluid or gas. The temperature of this media—whether it is hot oil, steam, or cold water—directly transfers to the valve body and, eventually, to the coil through thermal conduction. If you are pumping hot hydraulic oil at 80°C (176°F), the metal valve body will become a radiator, pushing more heat into the solenoid.

However, the most critical victim of fluid temperature is the seal. Seals are the rubber or plastic rings that stop the fluid from leaking. Different materials are designed to handle different temperature ranges.

- NBR (Nitrile): Great for standard oil but can harden and crack if the fluid gets too hot (usually above 90°C).

- FKM (Viton): Excellent for high heat and chemicals, often used in chemical processing or hot engines.

- EPDM: Good for steam and hot water but terrible for oil.

- PTFE (Teflon): Can handle very high temperatures but is harder and less flexible.

If you use a standard NBR seal in a high-temperature application, it might work for a week. But soon, it will bake, lose its elasticity, and you will have a massive leak. Conversely, if the fluid is too cold, the seal can shrink or become brittle. When selecting a solenoid valve, you must know the minimum and maximum temperature of the fluid passing through it. It is just as important as knowing the pressure. For specialized applications, like our Professional Hydraulic Relief Valve Supplier products, we strictly check seal compatibility.

What Happens to Solenoid Valves in Low Temperatures?

We talk a lot about heat, but low temperatures present a completely different set of challenges. In extreme cold environments, such as cold storage warehouses or outdoor equipment in northern winters, the solenoid valve faces a fight against physics.

First, there is the issue of viscosity. As the temperature drops, hydraulic oil and other fluids get thicker. Think of trying to pour honey that has been in the fridge. This thick fluid is much harder to push. The solenoid has to work much harder to move the plunger against this resistance. This can result in a slower valve response or, in severe cases, the valve might not open at all because the magnetic force isn't strong enough to overcome the drag of the thick fluid.

Second, moisture is an enemy in the cold. If there is any humidity in the air system or the environment, it can freeze. Ice can form around the plunger or armature, physically locking the mechanical movement of the valve. Additionally, standard seals can become hard as rock in low ambient temperatures. Instead of flexing to create a tight seal, they might crack or simply allow fluid to pass by. For cryogenic applications or outdoor winter use, we need to use specific low temperatures seals and potentially heater jackets to keep the valve operational.

Understanding Solenoid Coil Temperature Ratings and Insulation Classes

When you look at a datasheet for a solenoid valve, you might see a "Class" listed under the coil specifications, like "Class F" or "Class H." This is the temperature rating for the insulation system used in the coil. It tells you the maximum temperature the insulation can withstand before it starts to break down and fail.

This rating is critical. It is calculated by adding the maximum ambient temperature plus the allowable heat rise generated by the coil itself.

- Class F: Typically rated for a maximum hot spot temperature of 155°C (311°F). This is the standard for most industrial applications.

- Class H: Rated for 180°C (356°F). These are used in hotter environments or for valves that run on continuous duty where significant heat is generated.

If you put a Class F coil in an environment that is already 60°C, and the valve generates a 100°C heat rise during operation, the total temperature is 160°C. This exceeds the rating. The insulation will degrade, the copper wire might short out, and the coil will burn out. As a manufacturer, I always advise buyers to overestimate the potential heat. It is safer to use a Class H coil in a warm environment than to risk a failure with a Class F coil. The cost difference is small compared to the cost of downtime.

How Does Temperature Rise Affect Electrical Resistance and Power?

Here is a bit of science that directly affects your wallet. Copper, the material used in the wire of the coil, has a property called "positive temperature coefficient." This is a fancy way of saying that as the temperature of the copper goes up, its electrical resistance also goes up.

Why does this matter?

For a DC (Direct Current) solenoid:

According to Ohm's Law (Voltage = Current × Resistance), if the voltage stays the same (say, 24V) and the resistance increases because the coil got hot, the current must decrease.

Since the magnetic force of a solenoid is directly related to the current flowing through it, a hot coil is actually weaker than a cold coil.

If a solenoid valve gets too hot, its force might drop below what is needed to hold the valve open or pull the plunger. This can lead to the valve dropping out or "chattering."

This means a valve might work perfectly when you first turn on the machine in the morning (when it's cold). But after running for 4 hours and heating up, the resistance rises, the current drops, and suddenly the valve fails to operate the valve. This is a classic sign of heat-related issues. We design our solenoid valve coils with a safety margin to ensure they still generate enough force even when hot, preventing this affect solenoid performance drop.

AC vs. DC Coils: Which Handles Heating Better?

The power source—AC (Alternating Current) or DC—changes how the coil behaves regarding heat. AC coils and DC coils are fundamentally different beasts.

DC Coils: As mentioned above, their current is determined by resistance. They heat up slowly and steadily until they reach a stable temperature. They are generally simpler and very reliable, but they suffer from force loss as they heat up.

AC Coils: These are more complex. When you first energize an AC solenoid, there is a massive spike in current called "inrush current." This provides a strong kick to open the valve. Once the plunger closes the magnetic gap, the current drops to a much lower "holding current." This is governed by impedance, not just resistance.

However, AC coils have a vulnerability. If the plunger gets stuck and doesn't close all the way (perhaps due to dirt or ice), the coil never switches from inrush to holding current. It keeps drawing that massive inrush power. This generates a huge amount of heat very quickly—often enough to melt the coil in minutes. This makes AC coils riskier in environments where debris or mechanical sticking is possible. Generally, DC coils run cooler and are safer from burn-out, which is why many modern systems are switching to 24V DC.

How Do Duty Cycles Influence Solenoid Valve Heating?

Not all valves need to be "on" all the time. The duty cycle is the percentage of time a solenoid is energized versus the time it is off.

- Continuous Duty (100%): The valve is on continuously. It reaches its maximum heat and stays there.

- Intermittent Duty (e.g., 50%): The valve is on for 5 minutes, then off for 5 minutes. This allows the coil to cool down between cycles.

A valve designed for intermittent duty will have a smaller coil that packs a punch but cannot sustain the heat of being on forever. If you take an intermittent duty valve and leave it on for an hour, it will burn up. Conversely, a continuous duty valve is designed with more copper and surface area to dissipate heat effectively.

When sourcing valves for your control system, you must be honest about the application. If there is a chance the valve will be held open for long periods, you must specify a continuous duty coil. Using the wrong duty cycle rating is one of the fastest ways to kill a solenoid. For critical safety functions, like those found in our Double Pilot Operated Check Valves, reliability under varying cycles is paramount.

What is the Role of Proportional Solenoids in Temperature Sensitive Systems?

A standard solenoid is a digital device: it is either fully on or fully off. A proportional solenoid, however, can hold the plunger at any position in between. This allows for precise regulation of flow control or pressure. You can ramp the flow up slowly or dial it down.

Proportional valves are very sensitive to temperature. As we discussed, heat changes the resistance of the coil, which changes the current. In a standard valve, a small drop in current might not matter. But in a proportional solenoid, current is the control signal. If the current drops due to heat, the valve position changes, and your machine's speed or pressure drifts.

To combat this, sophisticated proportional controllers use "current feedback" or Pulse Width Modulation (PWM). The controller monitors the current. If the coil gets hot and resistance rises, the controller automatically boosts the voltage to maintain the correct current. This ensures the solenoid valve performance remains consistent regardless of the temperature rise. If you are using proportional solenoid valves, ensuring your electronic controller has this compensation feature is vital for accuracy.

Practical Tips to Manage Temperature and Prevent Valve Failure

So, how do we keep things cool and reliable? Here is a checklist for procurement officers and maintenance teams to ensure temperature doesn't ruin your day:

- Check the Specifications: Match the temperature rating (Class F or H) to your worst-case environment. Always allow a safety margin.

- Mounting Matters: Mount solenoid valves in a well-ventilated area. Do not box them inside a small enclosure without airflow. If possible, mount the coil vertically; heat rises, and this can help with dissipation.

- Voltage Control: Ensure the supply voltage is correct. Over-voltage (supplying 26V to a 24V coil) causes a massive increase in heat generation (watt output increases with the square of voltage).

- Consider Latching Valves: If a valve needs to stay open for days, consider a "latching" solenoid. It uses a pulse of power to open and stays open mechanically without power. No power means no heating.

- Fluid Compatibility: Verify your seal materials (NBR, Viton, etc.) against the fluid temperature range.

- Keep it Clean: For AC coils, keep the fluid clean. Dirt prevents the plunger from seating, causing high inrush current and burnout.

- Power Economy Modules: Some modern connectors reduce the power to the coil after a few milliseconds. It gives full power to open, then drops to low power to hold. This can reduce heat by 80% or more.

Key Takeaways

- Heat is Inevitable: All solenoid valve coils generate heat due to electrical resistance in the wire. This is normal, but it must be managed.

- Environment Kills: High ambient temperatures prevent the coil from cooling down, leading to insulation failure.

- Resistance Rises: As a coil gets hot, its resistance increases, which reduces the magnetic force in DC valves. This can cause the valve to fail to operate when hot.

- Know Your Seals: The temperature of the fluid dictates the seal material. Wrong seals will leak or crack.

- AC vs DC: AC coils risk burnout if the plunger sticks; DC coils are generally safer and run cooler but lose force as they heat.

- Duty Cycle: Never use an intermittent duty valve for a continuous duty application.

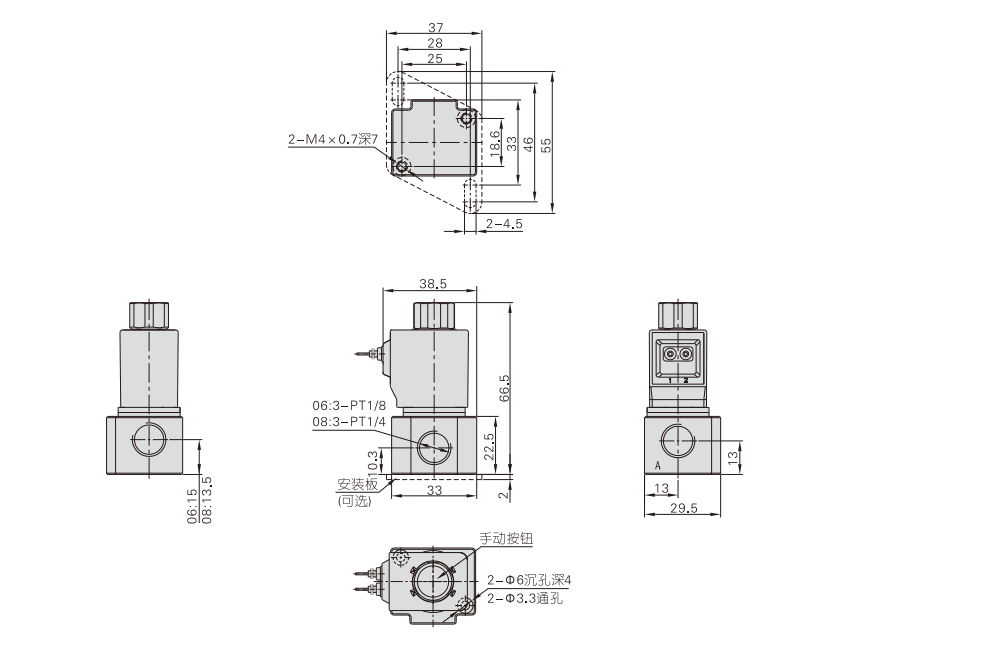

By understanding these factors, you can select the right solenoid valve that withstands the heat and keeps your machinery running smoothly. Whether you need a simple Solenoid Valve (Three Ports, Two Positions) or a complex Flow Regulator Valves, keeping temperature in mind is the key to long-term reliability.